Photographed by Jason Myers for MONEY

No. 1

Clarksville, Tennessee

Fifty miles northwest of the neon lights of Nashville, there’s a place where natural beauty coexists with a growing economy, unique small businesses are thriving, a cheap meal out rarely costs more than $12, and there’s always a trivia night, community event or concert on the calendar.

And, yes, you can actually afford to live there.

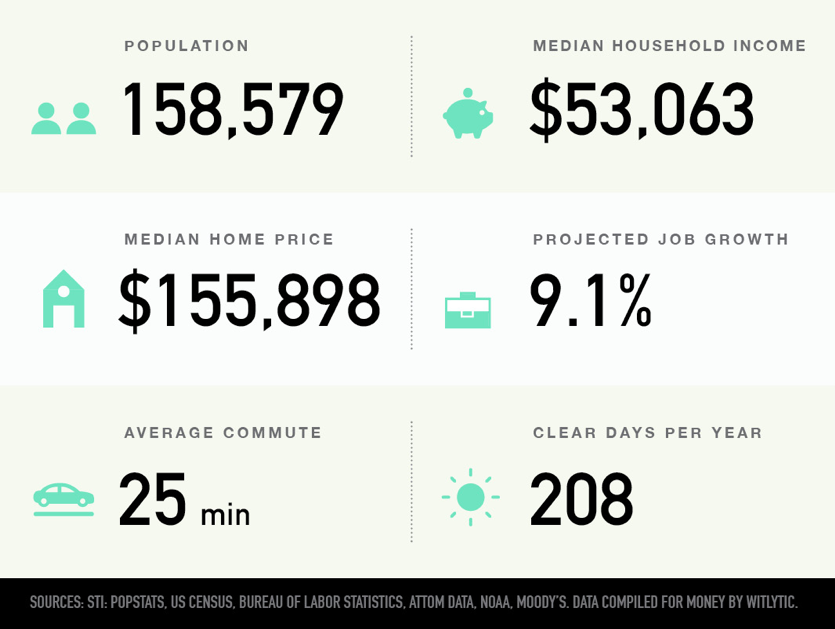

Clarksville, Tennessee might not be on your radar yet, but it should be. To all the millennials moving in, the city of about 160,000 people is a place they can afford to plant down roots. The average age of a Clarksville resident is only 29, almost a decade younger than the state of Tennessee as a whole. And guess what? They’re actually buying houses. Between May and July 2019, about one in every two Clarksville mortgages was closed by a millennial, according to Ellie Mae. That’s perhaps not surprising, since the average Clarksville home sold for just under $156,000 in 2018, according to Attom Data — which is nearly $100,000 below the U.S. median home price in the same year.

At Copper Petal, a trendy boutique on Clarksville’s walkable Franklin Street in the heart of downtown, founder Megan Baggett, 25, sits on a plush pink couch against an Instagram-ready black and white backdrop. Above her head are the bright pink words “Community + Confidence.” Baggett, a Clarksville resident since she was six months old, knows a thing or two about buying a house in the city: she and her husband Luke, who’s the third generation in a family of Clarksville home builders, recently bought their first home — and even they had to move fast.

“The housing market is just crazy right now,” Baggett says. “You can barely even keep a house on the market for longer than a week before it sells.” To keep up with demand, she says, her husband is working on building six different houses. The city of Clarksville covers a fairly wide geographical area, and contains neighborhoods featuring an array of homes: new Craftsman-style, grand estates, duplexes, apartment complexes, and more.

Located near Kentucky’s Fort Campbell, one of the largest military bases in the U.S., Clarksville has long been a beacon for servicemembers and their families. More than 68,000 retired military members call Clarksville home, according to a Tennessee Department of Economic and Community Development report. According to local lore, Jimi Hendrix himself settled briefly in Clarksville after being discharged from Fort Campbell, and was a regular performer in downtown clubs before moving to New York.

There are a growing number of reasons to live in Clarksville outside of the military. “We actually had someone come in probably three months ago from Atlanta,” says Baggett. “They were looking to move here and they had no connection here. They just came and they really liked it.”

The city is home to a sizable amount of Nashville commuters, so it seems inevitable that Clarksville would grow as Nashville does. (Jobs in the capital city have grown about 38% since July 2009, according to BLS data.)

Clarksville, which is projected to gain 90,000 residents by 2040, has its own growing industry, too. Jobs in the surrounding Montgomery county are estimated to increase by just over 9% by 2023, according to Moody’s Analytics. A new LG manufacturing facility opened in early 2019, bringing hundreds of jobs with it, and Google is set to open a $600 million data center on the northeast side of the city with about 70 highly-skilled positions within the next two quarters, according to a Google spokesperson.

The industry isn’t limited to tech and electronics, though. Clarksville is also a hotbed for small businesses, which can receive free guidance from the local chapter of the Tennessee Small Business Development Center, located at the Austin Peay State University and partially funded by the U.S. Small Business Administration. They can also get started by selling their wares at Miss Lucille’s Marketplace, an antique market that’s become known as a business incubator, with locals graduating from selling in pop-up booths to managing entire storefronts.

Clarksville’s charming downtown has come a long way since 1999, when a tornado damaged stores and forced businesses out. You would never know it walking the main strip today, which is home to breweries, restaurants, and local businesses. The downtown district seems allergic to chains.

“You’re not going to find a Starbucks down here,” says Tony Shrum, 34, whose record shop &Vinyl sits downtown at the corner of Franklin and North Second Street. “A revitalization of downtown is not a revitalization by putting corporate companies in here.”

And that’s good news for him. Renting a similar space in nearby Nashville would cost “three, four times more,” he says. Here in Clarksville, his bright and airy shop is filled with rows of vinyl, and the walls are decorated with American flag-painted slabs of wood — relics from the shop’s previous occupant.

“There’s people that want to move to a big city, but they don’t want to pay what it costs to live in a big city,” Shrum says. “If you want to be a hipster on a budget, here you go.”

The consensus is the same among everyone I talk to during my visit: Clarksville’s affordability is hard to beat, yet it’s not the only thing that makes the city special. There’s a unique charm to the place; it feels like the quintessential small American town. Not only are there small, locally-owned businesses, but public places where residents can go to relax, like the new park at Downtown Commons or the River Walk, whose paved path provides a beautiful view of the Cumberland River at sunset.

“I’ve tried leaving for 22 years and I keep coming back,” says Lorneth Peters, director of the Tennessee Small Business Development Center at Clarksville’s Austin Peay State University. “And it’s because of the feel. It’s not only the affordability, but you feel at home.”

A strong community seems to be the backbone of Clarksville, and it shows itself in the friendly lunchtime banter between regulars and waitstaff at the bustling Yada Yada Deli. It’s in the buzzing aisles of the local Target, where parents leaf through the backpack selection with their children and a couple tweens peck through office supplies for the perfect binder at the end of summer break. It’s in the way somehow everyone seems to know each other when they cross paths outside the Roxy Theater or hiking on the trails of Dunbar Cave State Park. Some people in town say the city’s friendliness is related to its military population; when a resident is deployed, the community steps in to help care for the family.

The same feeling of remarkable effort extends to Clarksville’s school system. In a city with 41 schools and more on the way, Clarksville’s educational system is performing well, even as the city grows. Clarksville students perform better on reading and math tests than state average, according to Ed.gov data, and the graduation rate is 95%.

Deciding on a place to live is a notoriously complicated process, and there’s no one-size-fits-all city out there. But Clarksville seems like a good fit for the residents choosing to call it home, and the city seems well-poised for an even brighter future.